|

|

|

| Rembrandt, Prodigal Son | The Amygdalae | Goya, Disasters of War |

| https://bit.ly/2Imuiwj | https://bit.ly/2EDeRfv | wdl.org/en/item/19462/ |

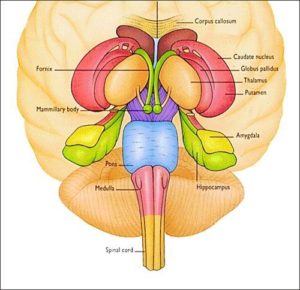

Among the different forms of altruism, perhaps the most dramatic is the donation of a kidney to an unspecified recipient. For that reason, Abigail A. Marsh, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Georgetown University, decided to examine the brains of nineteen altruistic kidney donors to see what neurological features might be connected to this remarkable behavior. She found a clear expansion of an almond-shaped part of the brain called the amygdala. (“Amygdala” is Greek for almond.)

The amygdala is associated with vigilance and emotion. It receives perceptions requiring a response of fight or flight. This “alarm bell” would sound in altruists at the perception of another person’s need but not in the brain of a psychopath. Worse, no restraint would inhibit the aggressive action of a psychopath, who would be essentially blind to victims’ fearful expressions. The amygdala is therefore the pivot between a willingness to help and a willingness to hurt on what Walsh calls a “caring continuum.”

Walsh and her colleagues obtained these results by using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a prominent method of measuring brain activity, and particularly its response to different stimuli. The researchers used identical, standardized face-imaging tests on the altruists and psychopaths. “Altruists and controls viewed fearful, angry, and neutral facial expressions” and found the opposite results in the same tests administered to psychopaths. In the case of these nineteen extreme altruists, the right amygdala is larger, and is more responsive to facial fear expressions than controls. In psychopaths the right amygdala is smaller and less responsive.

Other researchers have obtained parallel results. For example, Elizabeth Shirtcliff and her colleagues’ review article of 2009 summarized experiments that indicate a contrast in brain activity between empathy and callousness. Their sources identified a range of measures in two parts of the brain, the insula and the ACC (anterior cingulate cortex). In another review of many experiments, R. J. R. Blair states that the “callous-unemotional component” of psychopathy, which impairs empathy, “reflects reduced amygdala responsiveness to distress cues.” But he expands his focus from the amygdala to circuits connecting other brain regions. Poor responsiveness to distress cues, so prominent in psychopathy, are “associated with reduced amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC)” functioning. Instead of studying the brain in action, as it responds to stimuli, Sandra Thijssen and Kent Kiehl examined the brain at rest, that is, the default mode network (DMN). After testing incarcerated male adolescents, they found that disruptions in connectivity between the components of this network characterize psychopathic adolescents. Indeed, without therapeutic intervention, those disruptions would continue in the same persons as adults.

Because the volume, activation, and coordination of brain parts are measurable, the range of values from high to low potential for empathy can be considered a continuum. This sliding scale dramatizes the reflection that our language for psychology and behavior is older than the nomenclature of neurology. We don’t say a person’s action or mood was amygdalic or cortical. And scientists consider measurable activity in particular brain parts or their circuits as correlations with emotions, expressions, or behaviors — not causes.

Nonetheless, these findings suggest a spectrum from altruists to psychopaths that would look something like this.

• extreme altruists (e.g. living kidney donors).

• altruists (blood donors, first responders, philanthropists)

• prosocial, empathetic persons

• asocial egoists, individualists

• antisocial, callous persons

• extremely antisocial, callous persons: psychopaths

Altruists are indeed different from egoists, as I suggested in Introducing TEMPO and HUP and as Ayn Rand insists. But still, egoists are not psychopaths and altruists are not pathologically selfless. This scale describes a spectrum, and there are very few perfect types. Over the course of their lifetime, people move back and forth along the continuum of caring. Some egoists perform dramatic, altruistic acts, as when an entrepreneur becomes wealthy and donates generously to charity. One philosophical school, effective altruism, as articulated by Peter Singer in The Most Good You Can Do (Chapter 4, “Earning to Give”), urges accumulating wealth quickly in order to do more good than possible through a more modest or gradual approach. Nor is it necessary to be wealthy in order to share. Some of the most dramatic examples of generosity occur in dire circumstances.

Finding one’s path through life between these landmarks is a challenge. Heredity, neurology, the environment, and social constraints each play a role. We also have individual responsibilities. Beyond a decent concern for others, it behooves us to assure an environment conducive to healthy neurological maturation in the womb, in infancy, childhood, adolescence, and even into early adulthood because the brain is not fully formed until about age 26. Proper brain growth for the greatest number should improve mental health in the population and decrease psychopathy (see Hurt People). Then the moral factors favorable to individual rights and a just society can interact maximally to our mutual benefit.

References Not Linked.

Joshua Greene, Moral Tribes (2014), 122, 126.

Robert Sapolsky, Behave (2017), 44, 58.

Lisa Feldman Barrett, How Emotions are Made (2017), 17-24.