Our country’s founders foresaw a continuous contest between the federal government and the states. The government was to have only those powers ceded to it by the states, but it would claim more. Trust in, and the amount of, power accorded to the government is what divides conservatives from liberals (and their many derivative systems) in our country now. Conflict over racial difference and human rights has driven that division more than anything else.

Although the problem is much older, the most recent major turn occurred when the Supreme Court declared in Brown vs Board of Education (May 17, 1954) that education could only be equal if blacks and whites were schooled together. In the South, resistance was intense. Many whites retreated into what they called Christian academies to preserve segregation. Mississippi closed all public schools (Sept. 16, 1954). Virginia allotted public money to support segregation academies (January 9, 1956). Southern resistance to court-ordered enforcement of Brown also took the form of murdering civil rights activists, black and white. Gradually, the federal government actively enforced Brown and extended equal rights via the courts, the congress, presidential executive orders, and by dispatching soldiers.

At first, the Republican Party, founded by Abraham Lincoln, was the strongest proponent of civil rights. The staunchest defenders of segregation in the opposing party were Southerners called Dixiecrats. After a court ordered still-recalcitrant Alabama school districts to obey the Brown decision, there followed an eleven-day wave of bombings. On September 15, 1963, a Sunday, members of the Ku Klux Klan in Birmingham AL exploded a bomb that killed four girls in the 16th Street Baptist Church. The nation was outraged. Encouraged by the Democrat Lyndon Johnson, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of July 2, 1964, which banned segregation in public places and discrimination in employment. Even then, only 61% of Democrats in the House supported this action but 80% of Republicans. Again in 1965, still under Johnson, only 73% of Democrats as against 94% of Republicans passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965 to remove legalistic obstacles to black voter registration.

The Civil Rights act passed with the 1964 presidential primary campaigns in full swing. Eleven days later, the Republicans nominated Barry Goldwater, who filibustered against the Act, over runner-up Nelson Rockefeller, a moderate. Dwight Eisenhower’s former vice-president, Richard Nixon, backed Goldwater. Five states in the Deep South that had voted for the Democrat Kennedy in 1960 (Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina) voted for the Republican Goldwater in 1964, along with his home state of Arizona. Rejecting their segregationist tradition, the Democrats nominated Johnson, who won.[i] During the 60s, the parties, therefore, reversed their positions on civil rights. Among blue-collar workers about 60% voted Democratic in 1960; in 1968 it was 30%. African Americans went the other way. In 1960, one-third voted Republican; by 1972, only one-in-ten did.[ii] Segregationists fled the Democrats; African Americans fled the Republicans. Race was the pivot.

The cohesion of segregationist voters as they switched parties reflected an underlying belief in a standard American identity. Consciously or not, over time, a mythical type pervaded the country: white, male, Christians of northern European stock were held to form the American ideal.[i] “Their” women accepted and promoted this notion. History textbooks and scholarship exaggerated the influence of this group. New England’s sole experience was said to have shaped the new country. After they were physically almost eliminated, Native Americans were not mentioned except as “heathen savages.” Those enslaved and brought here forcibly from West Africa were viewed by Christian writers like Josiah Priest, as children of Ham, doomed in Genesis 9:25 to be forever “the lowest of slaves.” Mexican American ties to an Aztlan culture that linked the American Southwest to Mexico and the Spanish language was ignored. The ordinary European American identity that many assumed and propagated encouraged them to assert their own group’s interests and limit the potential of others.[ii] From their aggrieved viewpoint, Brown versus Board of Education forces them to educate their children together with those they scorn—violating, as they said, freedom of association. When the Nineteenth Amendment expanded the suffrage in 1920, women gained political equality with men — a monopoly lost. From this perspective, affirmative action (the phrase was coined by John Kennedy in Executive Order 10925 of 1961) constitutes government betrayal. Defenders of the ideal identity see it as reverse discrimination. For white opponents of civil rights, these actions amount to saying not that blacks are equal to whites, but that whites are no better than blacks. Worse, in affirmative action, they believe the government saw minorities, specifically blacks, as being preferable.[iii]

Sensing this resentment, Richard Nixon devised his “Southern Strategy:” Lose the blacks, win the white working class. He targeted, and often won, in his words, “Democrats, blue-collar workers, and working-class white ethnics.” Nixon implied that racial minorities sought not equal rights or opportunity, but superiority. “They refuse to start at the bottom of the ladder the way you did,” he lied. “They want to surpass you. . . . They want it [your success] handed to them.”[i] The need to interact with these “others” as equals inspired fear in those who saw them as threats. When stoked by demagogues, that fear becomes hatred. The toll on all concerned has been horrific.

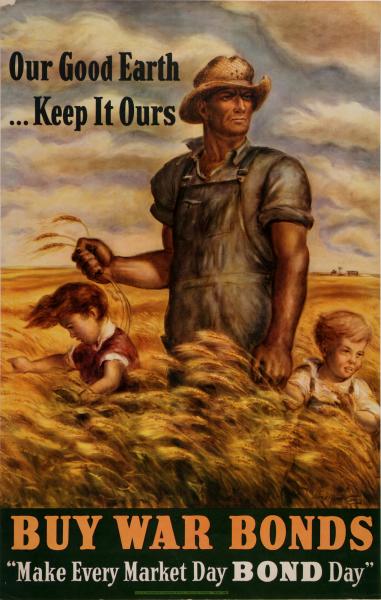

Condemning Nixon’s exploitation of white backlash is not a criticism of whiteness but of a false superiority—white supremacy. Some members of any group will exaggerate a natural pride in what they consider their outstanding qualities. In the U. S., historically, though, the white, male, middle-class, nuclear family was assumed to be the “American norm” used, sometimes unconsciously, to disparage others of different genders, ethnic backgrounds or skin colors and therefore to exclude them from the norm. Discrimination against others for the color of their skin is racism. This advertisement for U. S. war bonds shows how a white farmer and his children are considered typical and assumed to represent all Americans.

© John Steuart Curry. Chazen Museum of Art, Madison WI. https://embarkkiosk.chazen.wisc.edu/Obj1873?sid=11350&x=477858&port=1599

SAAM-2001.83_1 American Art Museum, Gift of Roger Genser–The Prints and the Pauper, 2001.83

The farmer stands with two children in the middle of a seemingly boundless field of wheat. His grasp of sheaves in either hand indicates ownership and power. The mother is lacking. The children imply a connection between the father’s genes and the land. The appeal for war bonds suggests that battle will keep the land “ours” for families like this one and their descendants. The non-white and other minority ethnic American combatants are omitted, here, from those whose land it is. Those who identify with this standard feel a loss to their identity as the government protects others and causes, they fear, this image to fade.

This ideal, and the anxiety occasioned by deviation from it, pervaded the entire U. S. What the South resisted openly, those outside the old Confederacy opposed covertly but with similar oppressive effect. Using silent shunning rather than actual legislation, whites confined blacks into segregated neighborhoods, ghettoes. The neighborhood schools they extolled were a cover for segregation. For that purpose, busing was no problem. Indeed, in the case for which the landmark Supreme Court decision was named, the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, had bused Linda Brown away from her neighborhood school to keep it white. Although the history goes back years, it was Boston’s 1974 confrontation over busing to bring blacks to white schools that focused national attention on this northern pattern. Busing was another way to achieve integration, and northern, white, ethnic neighborhoods resisted it fiercely.

Opposition to federal integration orders —anti-black animus— helped reverse the prestige enjoyed by the government since World War II. Whereas victory in war followed by the presidency of its allied commander, Dwight Eisenhower, and the economic growth that came from having the world’s strongest economy (and its only atomic weapons) had boosted the reputation of our government, things began to change in the 1960s. The war in Vietnam tarnished our military and cost our foreign policy much prestige. At home, three liberal leaders, including a president, were assassinated. Ronald Reagan blamed the government itself when he lamented its tendency towards “over-regulation.” In his inaugural address on January 20, 1981, he declared: “Government is not the solution to our problem: government is the problem.” Reagan thus applied white, working class and segregationist arguments against civil rights to many other areas where corporations and some churches opposed the state’s liberal efforts at regulation or reform.

To undermine the legitimacy of government, some have attributed to Ronald Reagan this remarkable statement. “Protecting the rights of even the least individual among us is basically the only excuse the government has for even existing.” It is curious how this statement turns back on itself. The government’s duty to protect the rights of every (even the “least”) individual among us is precisely the rationale for civil rights. Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King (had he not also been assassinated), and many other Christians would have caught this biblical allusion to the command that all should care for all.[i] Strange, then, that opponents of government neglect this moral responsibility.

Objection to Big Government became the springboard for many other conservative attacks on liberal programs. The conflict thus expanded from race relations and minority rights to the federal government’s relationship to local jurisdictions, corporations, and religious denominations. Businesses opposed government regulations requiring them to have clean, safe factories, to limit workers’ hours, to label products, to bargain collectively, to avoid polluting the environment. Other conservatives opposed government-enforced women’s rights (e.g. to abortion, paid maternity leave), gender equality, and gun regulation. This opposition can become violent. Timothy McVeigh, who bombed the Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995, did it, he said, “to put a check on government abuse of power.”

To conservatives, limitation of government is a primary civic responsibility. It follows the Ninth and Tenth Amendments that restrict government to those powers specifically enumerated in the Constitution. To liberals, such opposition attacks the statement in the Declaration of Independence that people create governments to secure the inalienable rights bestowed on all and the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee that “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” There could hardly be a more American debate than one opposing the premises of the Declaration of Independence to those of the Constitution.

Here is the dilemma that divides us today. Instead of seeing the protection of another person’s rights as a guarantee of our own, some feel a loss. It is a false supremacy, an assumed privilege, that allows some to neglect or even trample others’ rights because they are certain the system will defend their own. Our liberties are best protected when we understand our citizenship, indeed our humanity, as part of a net whose flexibility is its strength. Like every net, our social fabric has many intersecting knots. Each is composed of overlapping aspects of identity: gender, religion, homeland, family, neighborhood, school, and other ties. With enough empathy, we can see the whole differently from each knot. Our ability to grasp reality from all these angles can bind us as a nation.

[i] Matthew 25:40 “As you did it to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it to me.” Cf. verses 41-46.

[i] Lepore, 637-8.

[i] See the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 which initiated country-of-origin quotas, favored northern Europe, and excluded Asians altogether. For the characteristics of an American identity, see Que-Lam Huynh, Thierry Devos, and Hannah R. Altman, “Boundaries of American Identity: Relations Between Ethnic Group Prototypicality and Policy Attitudes,” Political Psychology, 36, 4 (2015), 449-468; doi:10.1111/pops.12189.

[ii] Huynh, et al., 449, 466.

[iii] For a more nuanced analysis of this Middle American perspective than this summary permits, see Arlie Russell Hochschild, Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right (2016), esp. 221. Hochschild notes in Mississippi the “perceived betrayal by the federal government,” and the sense that their type is disappearing, “There are fewer and fewer white Christians like us” (221).

[i] Jill Lepore, These Truths: A History of the United States (2018), 613-14.

[ii] Lepore, 633. These percentages are approximate.